PaaS vs. DIY IDP: The Fastest Path to a Self-Service Cloud

Key points:

- The Hidden "Integration Tax" of DIY: Building your own IDP isn't free; it requires stitching together disparate tools (Backstage, ArgoCD, Terraform), creating a "Franken-Platform" that demands constant maintenance and diverts senior engineers from revenue-generating work.

- Modern PaaS Offers Control Without Lock-in: Unlike traditional PaaS (Heroku), modern "Control Plane" solutions like Qovery run directly on your own cloud infrastructure (AWS/EKS), giving you the speed of a PaaS with the compliance and control of a DIY solution.

- Speed to Value: A DIY IDP typically takes 6-12 months to reach MVP, whereas an all-in-one platform delivers a working self-service cloud in days, allowing you to unlock developer velocity immediately rather than a year from now.

Every engineering leader has the same dream: a "Golden Path" where developers deploy code without waiting for tickets, wrestling with Kubernetes YAML, or accidentally breaking production.

The instinct is almost always to build it yourself. After all, your infrastructure is "unique," right? You have specific compliance needs, legacy workflows, and a team of smart engineers who love open-source tools.

But here is the hard truth: Your "unique" problems are actually standard infrastructure challenges that thousands of companies have already solved.

By building your own Internal Developer Platform (IDP), you aren't just building a tool; you are signing up to become a software vendor to your own internal team. You are trading a monthly subscription fee for years of maintenance, "glue code" debt, and the opportunity cost of your best engineers fixing deployment pipelines instead of building your product.

This guide compares the true cost of a DIY IDP against the modern "All-in-One" approach, exposing the hidden taxes of building from scratch and revealing the fastest path to a functioning self-service cloud.

The Reality of the DIY IDP

Building an Internal Developer Platform from open-source components appears cost-effective initially. As the tools are free and their flexibility is unlimited, the operating team retains complete control.

However, when using this strategy, the hidden costs emerge over time.

The Franken-Platform

A functional IDP requires multiple components that must work together seamlessly.

A portal layer acts as the main developer interface. Backstage, a project created by the Spotify teams, has become a default choice as it offers a plugin architecture and service catalog capabilities. As a limitation, Backstage requires extensive TypeScript expertise to customize and maintain its deployment, with added configuration needed to match specific organizational workflows.

The continuous deployment layer handles getting code to clusters. ArgoCD or Flux provide GitOps capabilities, but each requires installation, configuration, and integration with the portal and infrastructure layers.

The infrastructure-as-code layer provisions cloud resources. Terraform or Pulumi manage the underlying infrastructure, but connecting IaC execution to the portal and deployment layers demands custom integration work.

The orchestration layer runs the workloads. Kubernetes is the standard container orchestration solution, but abstracting its complexity for developers requires building additional tooling on top.

Each component works independently. Making them work together requires custom glue code, API integrations, and shared state management. This integration work represents the bulk of DIY platform engineering effort.

The Integration Tax

The integration tax refers to the ongoing cost of maintaining connections between various components of the platform.

When Backstage releases a new version, the portal needs updating, which may impact other plugins or integrations with other tools. Testing the upgrade requires validating the entire platform, not just the component being changed.

Each component evolves on its own schedule, and the platform team must continuously reconcile these changes. Security updates compound the burden, as vulnerabilities in any component may propagate between components. The platform team becomes responsible for security across the entire stack.

The Maintenance Trap

As the Platform Team builds out and maintains the platform, they become software vendors to their developers. They handle bug reports, feature requests, and support tickets. They document systems that only they understand and become bottlenecks when critical issues arise.

The maintenance burden grows as the platform matures. More features mean more code to maintain and more potential failure points. This compounds with the audience growth, as more users generate more pressure on the platform.

Engineers hired to build the platform spend their time maintaining it. The innovative work becomes a secondary occupation as routine maintenance and customer support take center stage. This lowers the ability to retain key engineers, as their interest in the daily work lowers without true innovation work.

The All-in-One PaaS Approach

The alternative to building from components is adopting an integrated platform that provides the integrations out of the box.

What All-in-One Means

An all-in-one platform integrates the portal, deployment engine, environment management, and cloud connection into a single cohesive product. The components are designed to work together from the start rather than integrated after the fact.

This integration eliminates the glue code that DIY platforms require. Updates to one component account for dependencies on others and security patches apply across the system. The provider directly handles the integration tax.

Speed to Value

The timeline difference between both approaches is substantial for growing engineering organizations.

DIY platforms typically require six to twelve months to reach a minimum viable state. The first months disappear into tool selection and initial setup, while integration work consumes the middle period, and stabilization and documentation fill the remaining time. Developer adoption begins only after a functional foundation exists, which only happens once this period is over.

All-in-one platforms provide value in days, as the installation typically connects to existing cloud accounts and Git repositories. This lets developers onboard onto the platform and deploy applications immediately.

This timeline difference represents months of developer productivity, especially for operating teams, who can regain time to dedicate towards business-specific efforts.

Control vs. Convenience: Addressing Lock-in Fears

The primary objection to platform adoption is loss of control. Which can be a valid complaint depending on the implementation decision of the chosen platform.

Traditional PaaS Limitations

Traditional PaaS solutions like Heroku provide simplicity by owning the entire stack. Applications run on vendor infrastructure, and customer data is hosted on vendor databases.

This model creates genuine lock-in, as migration requires moving applications, data, and configurations to new infrastructure. The vendor controls pricing, features, and availability, making organizations depend completely on their decisions.

The simplicity comes at the cost of control, compliance flexibility, and cost optimization. Many organizations outgrow traditional PaaS as requirements mature and feel constrained by their solution.

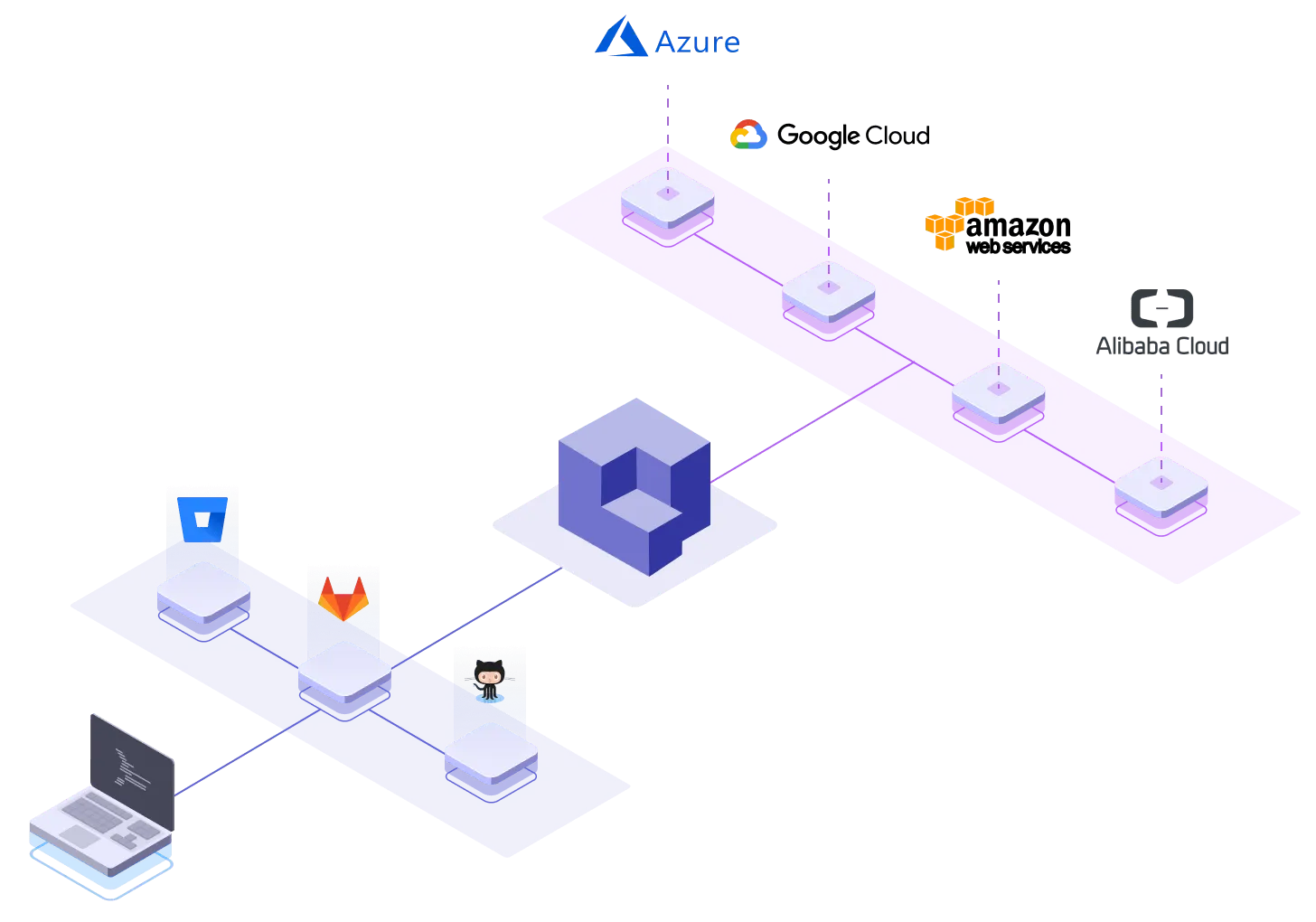

Modern PaaS on Your Infrastructure

Modern platforms like Qovery operate differently. The platform provides the control plane while the data plane remains in the customer's cloud account.

Applications are deployed natively on EKS, GKE, or AKS clusters. Data stays in your databases, secrets remain in your secret managers, and the platform orchestrates these resources without owning them.

This architecture preserves control while providing convenience. Customers retain security and compliance ownership while keeping control of any deployed underlying infrastructure.

The Un-Black Box

Unlike traditional PaaS, modern platforms provide transparency into their operations.

Qovery generates standard Terraform and Kubernetes manifests that you can audit. The infrastructure code exists in readable form. Teams can verify what the platform creates and modify it when necessary.

This transparency addresses the “black box” concern that prevents platform adoption. The platform automates infrastructure management without hiding how that management works.

Financial and Operational Impact

The build-versus-buy decision has concrete financial implications beyond tool costs.

Cost of Engineering

Platform engineering talent is expensive and scarce. Senior engineers capable of building IDPs command significant salaries, a team of two to three platform engineers represents substantial annual cost in compensation alone.

These engineers spend a year or more building the initial platform and subsequent years maintaining it. The total cost includes not just salaries but benefits, equipment, management overhead, and opportunity cost.

A platform subscription costs a fraction of this engineering investment. The comparison isn't platform cost versus free open-source tools. It's platform cost versus multiple engineer-years of effort.

Opportunity Cost

The engineers building your platform aren't building your product. Hours spent on maintaining the internal platform are not spent on features that differentiate your business.

Platform engineering is necessary work, but it's not differentiating work for your business. An internal IDP doesn't create competitive advantage, it creates parity with other organizations that have similar capabilities.

Buying the platform frees engineering capacity for work that matters. Product features ship faster, technical debt gets addressed, and innovation receives the attention it deserves.

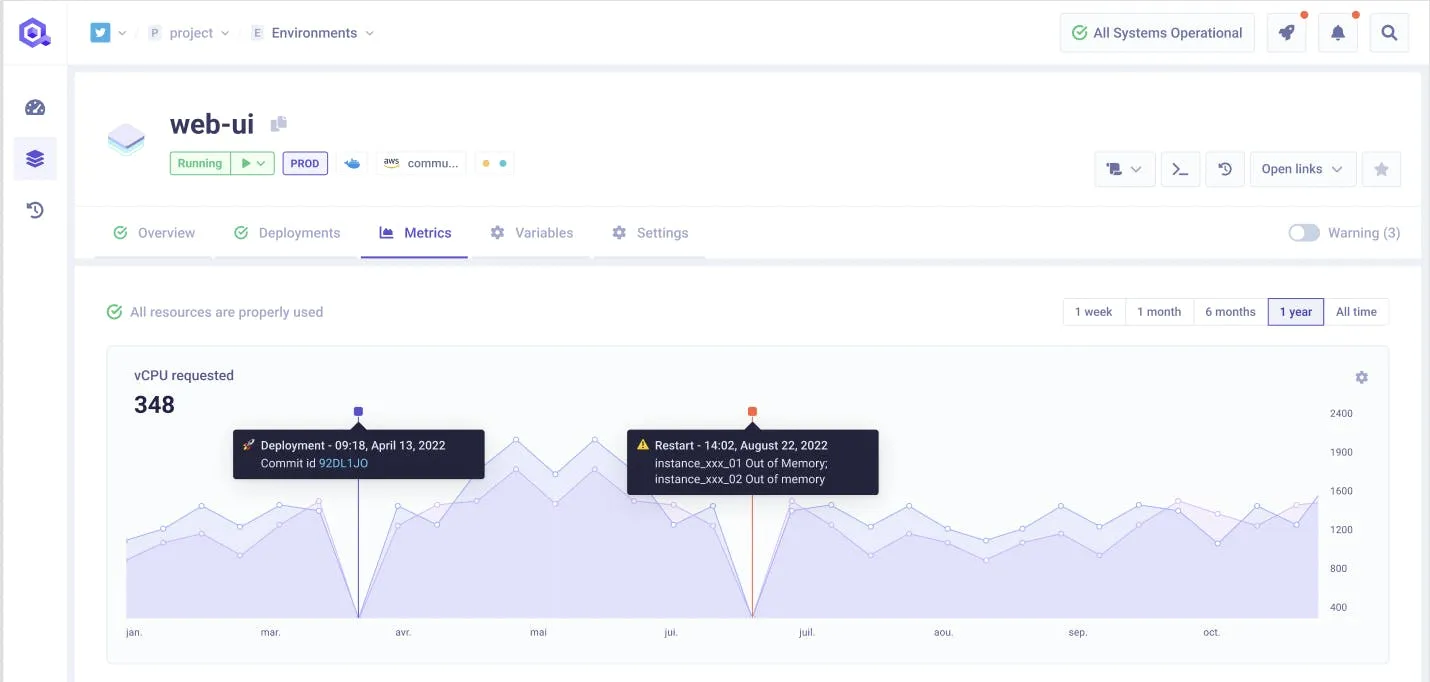

Day 2 Operations Value

Initial deployment represents a small fraction of platform value. Day 2 operations bring the ongoing benefit that they provide.

Ephemeral environments for pull requests take months to build in DIY platforms. Environment cloning for testing and debugging requires custom automation, auto-scaling based on demand needs careful configuration, and role-based access control demands security expertise.

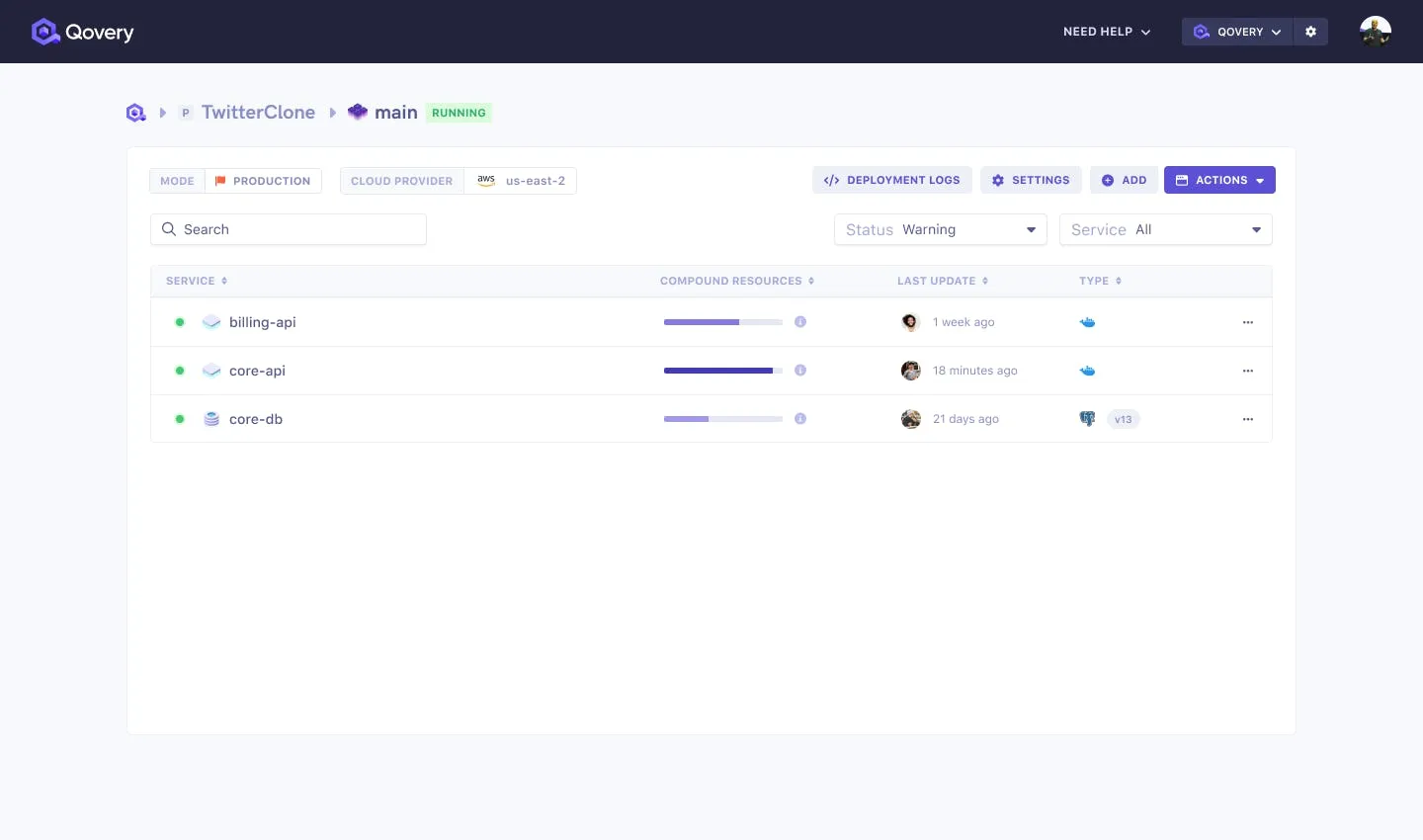

Qovery provides these capabilities immediately. Teams benefit from mature functionality day-one without needing to build it themselves.

The platform also offers solutions to monitor and keep costs under control out of the box, ensuring cloud spend stays lean as the engineering organization transitions to this new platform.

Developer Adoption

The hardest part of any platform initiative is getting developers to use it. A platform that developers avoid provides no value regardless of its technical abilities.

DIY platforms often struggle with adoption, as the interface reflects engineering priorities rather than developer needs, and documentation is often lacking. Rough edges accumulate because polish isn't prioritized, making it a harder sell for internal teams to adopt.

Qovery's interface is designed for developer adoption from the start. The UI prioritizes developer workflows, with an easy onboarding path for application development and strong documentation. The experience encourages adoption rather than requiring mandates.

High adoption rates mean the platform investment delivers returns, ensuring the platform implementation effort was not wasted and immediately created returns.

Conclusion

Building an IDP isn't just about picking tools. It's about the invisible work of integrating them and maintaining them indefinitely. The integration tax accumulates over years, consuming engineering capacity that could otherwise deliver business value.

The all-in-one approach provides immediate value without the integration burden. Modern platforms run on your infrastructure, preserving control while eliminating maintenance overhead. The speed difference between building and buying represents months of developer productivity.

Platform engineering should focus on organizational-specific workflows and policies, not recreating infrastructure capabilities that already exist. Buying the foundation lets teams build differentiation on top rather than duplicating commodity functionality.

Suggested articles

.webp)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)